A-naì-lí-sˆu (Lettera al proprio Dio)

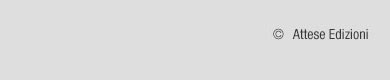

Nicola Cisternino, A-naì-lí-sˆu (Lettera al proprio Dio) 1

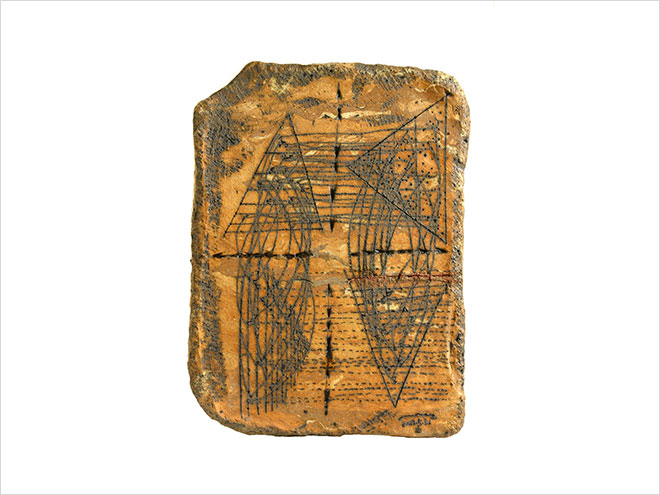

Nicola Cisternino, A-naì-lí-sˆu (Lettera al proprio Dio) 2

Nicola Cisternino, A-naì-lí-sˆu (Lettera al proprio Dio) 3

Nicola Cisternino, A-naì-lí-sˆu (Lettera al proprio Dio) 4

Nicola Cisternino, A-naì-lí-sˆu (Lettera al proprio Dio) 5

Prayer for Baghdad

a-naì-lí-sˆu (Letter to one’s God)

...Because it is in prayer that God weaves the threads of our fraternity: those between spouses, between parents with children, between brothers and sisters; even between brothers of faith and brothers of no faith, or between brothers of different faiths. Because the confines of the man of prayer are the confines of God, i.e. there are no confines. If in fact we have the spirit of prayer: because we then have the Holy Spirit of God within us, to suffer with sublime suffering, to pray for us, to initiate our very desire and to complete it. This spirit that soars above the abyss...

(David Maria Turoldo)

One afternoon I was reading the book Prayer as battle by Father Turoldo that for too many months had been waiting to be opened, preparing to give substance to the idea-project of a Prayer for Baghdad as requested by my friend and Bussottonian classmate Mauro Castellano, for the Biennale of Ceramics in Contemporary Art, when (terribly bitter…) comments and observations spewed from the radio to the effect that in the wicked (but planned and to what extent?) plunder of the “liberated” Baghdad nothing was being done to stop the looting of the famous Archaeological Museum. If smart bombs ever reached the atrocious dictator targeted for elimination, far more destructive bombs, in the bellies and caverns of history and memory, were reaching the very heart of the land of Uruk, of the city of Ur, of Babylonia, in today’s absolute “non-consciousness.” Who knows if the scribes of the cuneiform writing of the past — in fact, the actual invention of writing — had ever imagined that what they were promulgating to the humanity of the future, one day would never be able to be used at all against the constantly renewed “barbarians” of all time. Emotional and certainly shocking associations that leave a bitter aftertaste. In that same radio program, a famous Italian archaeologist who had worked very closely with those archaeological sites said: “…unfortunately, the so-called ‘smart’ bombs probably do exist but there certainly aren’t any ‘cultured’ bombs.”

A-naì-lí-sˆu (Letter to one’s God) is a composition-installation for piano (meaning Mauro Castellano’s, to whom it is “fraternally” dedicated), sand (a lot), monitors and “stone scores,” the latter made with terracotta in workshops and with the indispensable assistance of the skilled ceramic masters of Albisola, and that follows on, naturally, from my creation over the last few years of the Tibetan Prayers. Prayer as a “vibrant entity” and infinitesimal part of our intimate divinity, as we are taught by the ancient Tibetan Lama texts, and first and foremost by the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

A-naì-lí-sˆu (Letter to one’s God) is the name of a 7x5.6 cm terracotta recipient-envelope (currently of Louise Michail’s famous collection of cuneiform tablets) of unknown origin from the Paleo-Babylonian period, that contains a still well-sealed (not all “messages” are meant to be read) and just as small “illegible” tablet, illegible like the name of God according to the teachings of the Torah.

For many years I had hoped to create some of my Sound Graffiti scores — the writings with which my compositional research can be easily recognised from its very beginnings — on stone (certainly the most appropriate material); I made only two small experiments on slate tablets “taken” from the island of Saint Michel a few years ago.

In this case, the cuneiform alphabet is freely used to transform it from the visual dimension of the “reading” to the sound dimension, that original one of the “Word,” to make it linear writing – beyond any notational simulacra — i.e. a transition of thought and action of the act of the imagination and listening (Absolute Silence) to a manifestation of sound (Music and Singing).

A-naì-lí-sˆu (Letter to one’s God) can be performed only in the concert version (the “tablets” as a score) or in its “complete” traditional concert-installation version based on the following actions:

a) in a scene full of sand there is, in the centre, a piano under which fragments of 4 terracotta tablets (a good portion of which are buried in the sand) are sticking out from the small dunes. The same number of monitors (4), semi-buried in the sand, are located around and not very far away from the piano. A child (5-6 years old) or — as an alternative, the actor who in this case moves around the instrument — is playing under the piano and discovers the “tablets.” The first one (and so on) is offered to the pianist when he arrives; the pianist puts the tablet on the podium and performs the composition.

b) A few seconds after the beginning, the first monitor turns on to display the image of the typical “snowy static” (the dots are, however, the colour of the sand, like grains…); gradually, as the composition is played, the “pulverised” image condenses into that of the tablet… and remains fixed.

c) At the end of the performance of the four “tablet-scores,” the monitors (which have also become “tablets”) that have gradually been “activated,” remain on with a shot of the tablets in the gradual and complete darkness of the hall.

Nicola Cisternino

A-naì-lí-sˆu (Lettera al proprio Dio) by Nicola Cisternino was made in Albisola in 2003 during the 2nd Biennial of Ceramics in Contemporary Art.