Domenica Aglialoro

Domenica Aglialoro, 193 Days from the Massacre of the Silencio at Caracas

Domenica Aglialoro, 193 Days from the Massacre of the Silencio at Caracas

Domenica Aglialoro, 200 Days from the Massacre of the Silencio at Caracas

Domenica Aglialoro, 200 Days from the Massacre of the Silencio at Caracas

Domenica Aglialoro, 200 Days from the Massacre of the Silencio at Caracas

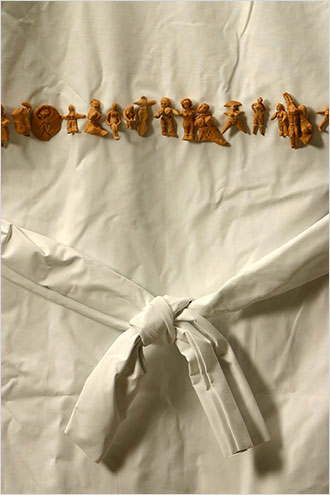

My ceramics are female

I have been working with ceramics for around twenty years yet I still lack the nerve to call myself a ceramicist. The ceramicist works at a specific trade that requires time, study, experience and endless patience. I instead use the basic techniques of ceramics and share the true ceramicist’s love of the material because ceramics is a passion. The manual labour is a pleasure for me: I model small objects with which I make large assemblages and I sew them into embroideries on cloth, in this case straightjackets. I have a very intimate relationship with ceramics that is conducted in my own home, on a drawing board that is always very clean and tidy, despite clay being a material ill-suited to such conditions. A bag full of clay for me contains the whole of the visible world and this permits me not to leave the house in search of the objects of the world. I bring to ceramics all the conceptual charge of my work that has as its theme the feminine. Hence I can say that my ceramics are female.

Domenica Aglialoro

Getulio Alviani

Getulio Alviani, 1.2.3.4 (inscritto nel cerchio)

Getulio Alviani, 1.2.3.4.5 (inscritto nel cerchio)

Getulio Alviani, 1.2.3.4.5.6 (inscritto nel cerchio)

El Anatsui

El Anatsui, Personal security

El Anatsui, Personal security

Perhaps clay’s most remarkable property is fragility, especially after firing — ironically the stage at which man thinks he has taken it to a “sophisticated” or “developed” level. Clay in today’s circumstances is not won in the built-up and high-rise urban terrains but in open pristine, lowly country side pits. But finished products from it, especially shiny glost ones, are almost all consumed in cities and not in villages.

I grew up in a countryside location and do not remember that there was any violent crime at all. As an adult with lots of encounters with urban milieu, one of the intriguing features of the culture of urban society is violent crime. Probably the most thriving industry in a world which is either urbanized, or is constrained by circumstances to gradually pretend some urbanization, revolves around security — especially at individual level.

I believe that unlike war, which is a public and open project in violence, security is at base a private issue — it is rooted in the individual and his ability to secure a territory around himself. At this level, it is a most vulnerable commodity. All kinds of gadgets have continued to be contrived to keep this personal space inviolate. The more precautions the more the vulnerability; the more the build-up the more the fragility.

El Anatsui

Nicole Awai

Nicole Awai, Oozing red, white and blue: recession, incursion, infraction 1

Nicole Awai, Oozing red, white and blue: recession, incursion, infraction 2

Nicole Awai, Oozing red, white and blue: recession, incursion, infraction 3

Perspective and Periphery: contemplation of the ooze

I have always been interested in perspective (point of view) and periphery (view beyond a point, elusive view), visually and conceptually. My work is an investigation and sometimes an observation of the passage between the two, periphery and perspective.

I am attracted to and often use objects such as dolls, ornaments, medical procedure mannequins, wig stands, historical and religious artifacts and toys in my work because they are imbued with cultural significance and/or meaning. In 2000, an object that I have been fascinated with since childhood, the Angostura ornamental rum bottle, made an appearance in a triptych that I painted entitled, They gave me a glass of rum, and one said to me, what did I think about all this? The quote is from Colin MacInnes’ Absolute Beginners.

The climax of the book becomes an experience of the passage between perspective and periphery. An eighteen-year-old street photographer helps a black acquaintance escape the wrath of the angry white crowd during the onset of the Notting Hill race riots in late 1950’s London. They take refuge in a basement where they find “a sort of West Indian war cabinet in progress.” The white boy overhears a conversation that one of the cabinet has with family members in Jamaica, “I wondered how my own people, out there in Kingston, surrounded by thousands of black faces, would be feeling when the news of it got around?... how all the whites in all those places would be treated, too? Because one big mistake a lot of locals make is to think that all Spades work on London Transport… whereas stacks are business and professional men, who know all the answers.”

In the triptych, the bottle image is painted so that it is in the extreme foreground, as if it is emerging from the surface. The bottle seemed to want to escape the painting and take on physical form — so it did. In Washed and Unwashed, I made two replicas of the bottle in clay from press moulds. One is painted to look like the bottle (the black version) the other is “white washed” in a much lighter tone.

This was followed by the multimedia bed installation Oozing Red White and Blue. On top of a rectangular mat made of banana leaves on a red satin-covered full sized bed are twenty bottle figures arranged in four rows (five deep). The figures are painted in a range of flesh tones that allude to chocolate, caramel, toffee and nut covered candies. The luscious sentinels are each discharging a different coloured, creamy, viscous ooze of red, white or blue. Some of the figures appear to be cracking, disintegrating from the force of the discharge. Some seem to be completely overwhelmed and enveloped by the ooze. I think that the ooze is elusive, it moves imperceptibly. I think that it is happening all the time and we cannot see it because it is constantly occurring in the glimpse space, in the shift, in the periphery. Metaphorically and mythically, the ooze captures a liminal event, a moment of flux. The ooze in nature can misplace, replace and relocate as well as create balance. In the body, the ooze breaks surface tension, enables cohesion and integration, creating an ideal environment. When a corrupting element or event occurs, when infected and thrown out of balance, the ooze suffocates, overwhelms and can even obliterate a thing out of existence or it can give something new life.

In Albisola, I was thinking about the ooze as a corrupting event — enter the Disney Tarzan action figure. The action figure probably originated from a Mac Donald’s Happy Meal or a Burger King Kid’s Meal (I found it on the street in Brooklyn). I have always wanted to realize the oozing bottle figures as something much larger. In Albisola I had the opportunity to do that as well as to extend and evolve their meaning. I made a series of drawings in which I introduced Tarzan into the ooze of the bottle figure. Both the rum bottle and the Tarzan action figure are symbolic of commerce and culture. The Tarzan figure appears to be moving through the bottle form, emerging and receding, engaging the ooze, implying and relating the dynamics of power — creating an incursion, a recession and finally an infraction.

Clay, as a medium always seemed right for this project. When master ceramist Danilo Trogu informed me that the only way to make these objects was to hand-build them, I was so excited. It seemed a way to physically engage meaning, to experience the ooze. There is unpredictability in the ooze as there is in working with clay. I always arrive at a point where the means (the materials) and the meaning come together and the artwork takes on life and it tells me what it wants to be. I give over to the process and become less attached to a specific outcome. At the end of the process, I had a hard time pulling myself away from the ceramic studio because the three sculptures of Oozing Red, White and Blue: Incursion, Recession, Infraction had much more to tell me.

Nicole Awai

Roberto Bertagnin

Roberto Bertagnin, Architettura

Paolo Bertozzi e Stefano dal Monte Casoni

Paolo Bertozzi e Stefano dal Monte Casoni, Potpourri

Bili Bidjocka

Bili Bidjocka, Zebra-skin

Bili Bidjocka, Tiger-skin

Bili Bidjocka, Leopard-skin

Bili Bidjocka, Zebra-skin

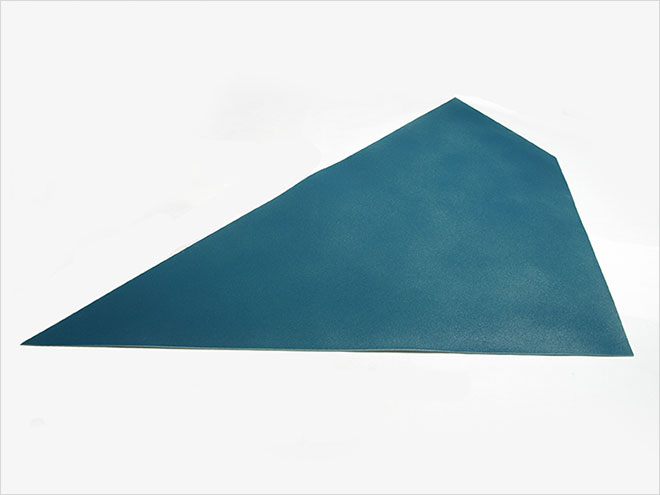

Pelle

(...) I would like to stay with the same idea I used for the 1st Biennale and to continue with the Skin series. The shape will be the same as the first dress but this time it would feature different patterns: zebra skin, leopard skin, human, and so on, and some typical “jungle style” camouflage. The sheet for each dress is about: 2.10 x 80 cm. As I see all the dresses as one single piece, in the end, it will be a kind of monumental work. There is one pattern based on human skin that I think might be difficult to reproduce in ceramics so I’m thinking about the photo transfer system; transferring the image of human skin rather than trying to reproduce it by ceramic painting (...)

Bili Bidjocka

Adriano Bocca

Adriano Bocca, Concetto rurale

Adriano Bocca, Concetto rurale

Tiziana Casapietra: The work that we selected for the Biennale is called Rural Concept and dates back to 1972. Can you give us some background about this creation and the period in which it was made?

Adriano Bocca: I spent my youth with artists who worked in Albisola at that time and, in particular, with those for whom experimentation was something outside the realm of painting.

TC: Didn’t you ever think of this work as an intentionally desecrating act with regard to a figure that then became one of the most important interpreters of contemporary art?

AB: Anyone who knew Fontana realised that he would never have considered anything to do with art as desecrating. Although he couldn’t stand vulgarity, he was very permissive as far as art was concerned. In those years, I preferred to follow Fontana and Manzoni. In Albisola there were also painters like Sassu or Capogrossi, but when you’re fifteen or sixteen years old, you always choose the extremes. I did what I did with Fontana in order to re-close the space that he had opened.

TC: What did you receive from the Albisola of the Fontanas and the Manzonis?

AB: In those years I was lucky to work in the Ceas laboratory where I could meet men who, like Fontana, were extremely generous with young people like me who were starting to do something. However, their friendliness was offset by extreme rigour. In addition to Fontana, people like Crippa, Garelli… also worked in that laboratory. Then you’d go to Bar Testa where, among others, you would find Fabbri, Capogrossi, Mario Rossello and Dangelo. We lived in close contact with these people the whole working day. Then, if I was lucky, I would even be able to cadge a dinner from Pescetto and continue learning.

TC: Tell me about Ceas.

AB: Ceas, a group of associated ceramists, was a team consisting of three people: Pedrin, a very good wheel turner; Mantero, a kiln man, because that laboratory still fired with wood; and then Platino, the colour man, who prepared the mixes. Here, the artists had remarkable technical support.

TC: Is this what you call the “school” where you were trained?

AB: Yes. You would arrive there in the morning and you stayed the whole day with these people who knew all the techniques and all the tricks, but who also had the skill to invent. At the end of the day if my work didn’t turn out the way it should have, Mr. Platino would put his hand on top of it and smash it. It was a tough school, a school of life.

TC: How did those years end? What happened afterwards?

AB: Tullio Mazzotti and Fontana controlled everything. But there was also a great gallery man like Cardazzo and an artist like Jorn. Between 1967 and 1973, all these personages passed away. Without any driving force, Albisola started going through a crisis. This is where Calice Ligure comes into the picture, hosting a new generation of artists including Mondino, Arrojo, Rougemount, Moncada and Dova. In this case it was Scanavino, a native of Calice, who kept things together. I went to Calice Ligure in 1971 to present an exhibition at the Gallery of Franz Paludetto where we met painters such as Nando De Filippi. Instead, there was a void in Albisola during that period, and so I started doing things to attract these artists who in Calice worked with the galleries of Paludetto and Remo Pastori. After all, Calice is just 26-27 km from Albisola. I liked the idea of bringing artists back to Albisola to teach them how to work ceramics. This is how the generation of the Seventies and Eighties was formed in Albisola, and that for us was very gratifying.

TC: Who was working in Albisola between the ’80s and ’90s?

AB: Eduardo Arrojo and Aldo Mondino were two of some of the most important people who I introduced to ceramics. All these artists ended up leaving some traces of their work in Albisola.

TC: With regard to your experience in Albisola during the years of Fontana and Manzoni, you tried to compensate for the void that had emerged in the ‘70s by bringing artists back to ceramics.

AB: Fabbri and Rossello were the survivors of Albisola’s golden period. One morning I asked Fabbri to help us to fill this void. When I asked him to help, I remember that Fabbri replied by telling me something important: “Look Adriano, now it’s up to all of you, we already did our part.” And so, based on his answer and out of respect for tradition, we rolled up our sleeves and organised a myriad of exhibitions starting with Ten personages for a museum where a re-interpretation of ten of the greatest personages who had worked in Albisola affirmed a new presence. Meaning us, the youngest ones, like Scrofani, Aonzo and Viale. Wifredo Lam was still alive during that period. I remember the bread exhibition and all the bread sculptures that we made and that Lam had also been involved with. This extensive period ended with the exhibition organised in 1990 by the Chamber of Commerce entitled Albisola. Artists. Ceramics. That exhibition included many artists, meaning any and all those who had worked with ceramics in Albisola.

TC: What happened afterwards?

AB: I had hoped for the same thing that happened with me, that some young people would have the same passion for tradition, for continuing a beautiful story: a story that grows through us.

TC: Then you left ceramics for painting.

AB: Today, most of my activities revolve around painting while I use ceramics only when it helps to explain what my pictures are relating. After the ‘80s no one talked about art any more. Instead, everyone talked about the market, money, and possible or impossible careers. I felt a sense of decadence spreading throughout Europe and the United States. This was one of the reasons why I decided to go to Asia, a world unaffected by fashion and the laws of the market, in order to study different cultures, to learn new painting techniques, and to dream new dreams.

Andries Botha

Andries Botha, Towers

Andries Botha, Towers

Andries Botha, Towers

Andries Botha, Towers

Towers

It has been some time since I last worked with ceramics. The medium suggested a range of metaphorical possibilities; earth subjected to intense heat, the alchemy of metamorphosis, rigidity, vulnerability and fragility.

September the 11th has changed our world, fractured our organizational systems and social logic. I wanted to make a work that positioned me/us/them/you as complicit elements within the implosion of a system of reason. This extreme social act or assault on a dominant social order challenges the organization of our philosophical systems. I tried to position the work as a metaphor of fractured or injured logic, expressed as a unit of measurement repeated in space as a modular, repetitive structure. A modular unit is defined as a square, expanded into a cube and then extrapolated into space as a tower, a visible ordering or organizational principle.

Deconstructing a specific formal understanding or conceptual tradition of ceramics and beauty suggested additional possibilities for engaging this logic as an ideological or cultural construct. Collapsing my manufactured tower and then methodically reconstructing the broken pieces into another tower, raises for me the interesting intersection of reality and virtuality. The obsessive and meticulous nature of the reconstruction process allowed me to indulge my own interests in labour (craft) as a physical construct for time that is made visible in a universe of individual ordering.

Toying with the ideas of reality and virtuality (or illusion) is more than likely a reflection of how my own embattled ideas of truth that are informed by popular electronic media images. Televised images of reality that persistently assault the passive space of our individual domestic interiors, conflates reality with entertainment. Re-representing the reconstruction of two towers as reality or subject (one reconstructed tower and one electronically projected tower), allows me to toy with the idea of tragedy as inherent within our accepted notion of order embodied within our logic, that which our rational sciences affirm and which formulates our definition of physical and emotional security.

Andries Botha

›› More Project - page: 1 2 3 4 5 6