A Tête-à-tête with paperweights and the brains of Alberto Viola

Museo della Ceramica di Savona

Roberto Costantino

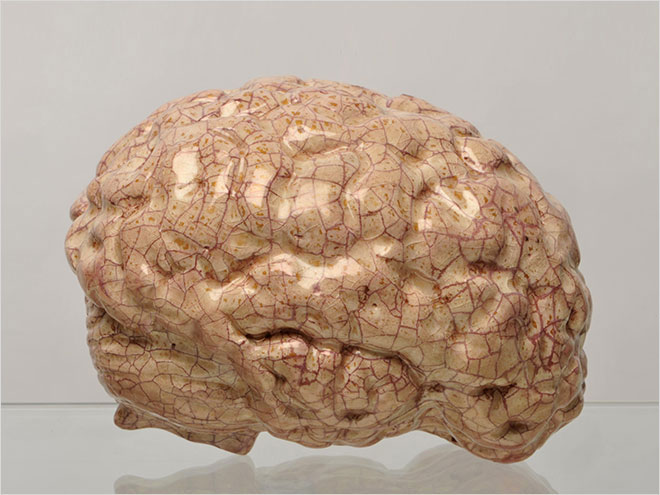

Alberto Viola, Paperweight, Attese Edizioni Collection, Museo della Ceramica di Savona

The sad little tale of the paperweight

Once upon a time, to stop cards from flying off the table, various objects and things were used and adapted, what they all had in common, naturally was that they were quite heavy. These are the kinds of objects and things that we still call Objet Trouve – from pebbles collected on the beach to weights, to give just two examples.

It is in the mid-nineteenth century that artisans began to produce paperweights. In particular, glass artisans, especially from France, but also from Venice or in the small Altare that began to work and shape paperweights, usually oval or sphere, which incorporated and sealed floral compositions formed by glass cuttings. Although, in addition to these Millefiori, there were also glass paperweights containing fruits, insects but also cameos, medallions, and metal or ceramic plates.

From that moment on, people began producing Presse Papier worked as micromosaics on tiny cards, paperweights molded and carved in noble or silvered or gilded metals, in malachite or in marble, but also in crystal to mimic precious gems or pearls.

Regardless of the material they are made of, paperweights, even today, are produced to serve as souvenirs or trinkets, even if, more often than not – unlucky for them – they constitute one of those “good things of bad taste” that we are very familiar with thanks to Christmas presents more often than not from Grandma Speranza.

Today, much to our dismay, the paperweight often takes on another role – the paperweight that comes started out as souvenirs or trinkets but can now be found in any museum gift shop or given out as a free gift by businesses – remembered as horrible objects, made on measure and ad hoc.

In any case, in addition to these kinds of paperweights, the Objet Trouvé also continued to be seen in action, as if to reiterate the uselessness of paperweights. As had happened to the close relatives of the paperweight- the Doorstops and the weights of times gone by- even the paperweight had become merely a functional item, when they were needed to exert their weight on those cards that would keep flying off the table.

Paperweights and design

The paperweight is a type of object that design companies have snubbed if not neglected completely.

Among the masters of design, which in other words means the older generation, are those who have faced this object head on, or at least touched on it in the world of Product Design. Even though they have existed for a century, the paperweights that have been designed to serve their purpose, cannot boast the signature of an author that is worth remembering, are extremely rare.

A few things by Gio Ponti, Piero Fornasetti, Ettore Sottsass, Angelo Mangiarotti and Enzo Mari made it to our desks. Even though the latter can boast an enormous collection of paperweights – faucets, bricks, clamps, irons and recycled industrial waste – that takes us back to the starting point, or to the Objet Trouvé and the Do It Yourself attitude that marks the history of this otherwise mistreated object.

Paperweights and brains

In recent years we have been lucky enough to see another paperweight, in a great exhibition, “Ultrabody” curated by Beppe Finessi in the Visconti halls of the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, on the bright, ultramundane runways of Design-week.

It is an enamelled ceramic paperweight in ancient rose that sparkles with gold – a paperweight true to form and that weighs about as much as a man’s brain – 1150 grams.

It is no coincidence that this object came to light only to be paperweight, even though the architect-ceramist Alberto Viola has re-designed and reproduced them in a series. He created a differentiated series, a limited edition of brains that serve as paperweights, each one different to the next.

To reproduce his own brain as a paperweight, Alberto Viola focused on the innumerable convolutions, furrows folding fissures, which mark the cerebral cortex in all its splendour.

What there is to see, in this case, is precisely this cerebral cortex, responsible for complex cognitive functions – sometimes, to our utmost regret – as thought, consciousness, memory and language. And it is precisely with this multifaceted role of the brain that Alberto Viola wanted to deal with, even here.

The architect-ceramist, once a disciple of Soto Dogen Zenji, the father of Zen meditation, emptied the ceramic brain of all that would have ruined it in the oven, mindful of the retreat where he emptied his own brain of everything that could be harmful to him.

Alberto sat in front of a white wall, for at least six hours every day, also because nothing else is more important in the life of a Zen monastery than the Shikantaza, to “simply sit”. And, while “simply sitting”, Viola remained immobile for a long time and has completely immobilized the brain, just like a paperweight that, in turn, must “sit”, motionless, to immobilize piles of sketches, annotations and notes left out.

In short, this ceramic work could “simply” be a sort of self-portrait of the author as a paperweight or brain. It does not matter anyway. Paperweight or brain, whichever it is.